The Allegheny County Department of Human Services (DHS) funds programs to assist young adults who are transitioning out of the child welfare system (also known as transition-aged youth) to secure employment, education, housing, behavioral health services, financial advice and more. Despite these service offerings, transition-aged youth have higher rates of homelessness, substance use, mental health challenges and incarceration, as well as lower rates of high school graduation compared with people who were not involved with the child welfare system. While targeted services are important, some human service needs result from poverty, which can be mitigated by providing direct financial assistance.

What is this report about?

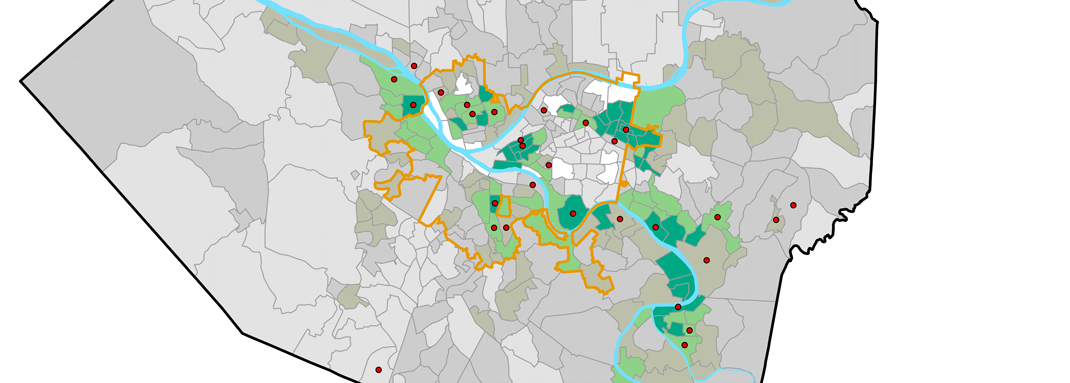

In the summer of 2023, DHS launched a direct cash support program called Cash Assistance for Allegheny Young Adults (CAAYA), which provided a one-time payment of $4,000 to young adults, ages 18 through 22, with a history in the child welfare system, who were experiencing homelessness or were young parents who had an open case with Allegheny County’s child welfare office. In this report, we present a mixed-methods approach to evaluating the impact of CAAYA, including longitudinal surveying, a quasi-experimental analysis of administrative data in the Allegheny County Data Warehouse, and semi-structured interviews with cash recipients.

What are the takeaways?

- CAAYA recipients demonstrated significant financial need. At the launch of the program, only 35% reported being currently employed and only 29% reported being in school either full-time or part-time. Those who had some form of formal employment in the 12 months before the program had mean annual earnings of $10,174. Twenty-eight percent had one or more children.

- CAAYA recipients also lacked financial support within their community. Two-thirds of recipients reported not knowing anyone who would lend them $500 in a time of crisis.

- Overall, the program encouraged about 100 individuals to open a bank account. Seventy-five percent (n = 774) of recipients chose to receive the money via bank account transfer and 25% via a virtual gift card.

- Recipients used the cash assistance quickly. On average, $2,769 of the $4,000 was spent within the first month.

- Car-related expenses ranked as the number one item for planned expenditures, and there was a 41% relative increase in car ownership three months after receiving the money.

- The program improved self-reported well-being after receiving financial assistance, but the effects faded in the subsequent months.

- CAAYA recipients increased their use of mental health outpatient therapy by 7% compared to a control group of individuals who were narrowly ineligible for the program. There was no change in utilization of crisis and inpatient services. In contrast to self-reported well-being, the program’s impact on usage of outpatient mental health services persisted for at least eight months after receiving funds.

How is this report being used?

As a result of this program, we are exploring additional opportunities to leverage cash assistance with this population to increase engagement in holistic supports and services. We are also considering longer-term programs with more frequent, smaller payments to targeted populations. For future programs, we hope to receive state waivers for the impact of cash assistance on public benefits, especially if a program is designed to include ongoing payments.

For other local governments or providers who are considering cash assistance programs, we hope this report serves as a resource for program design and evaluation. Local governments should note that the success of the CAAYA program would not have been possible without our partner organizations. Trust in government significantly impacts the accessibility of services, particularly for marginalized communities. When first hearing about the cash assistance, many individuals who were eligible to receive the money thought that it was a scam. This skepticism was eased by having multiple trusted intermediaries ensure that it was a real program and that they should apply.