In May 2022, Allegheny County assembled a taskforce of leaders to reduce intimate partner violence (IPV) through improved coordination, information sharing, training, and implementation of interventions that target both those who use violence and those who are victims or survivors of it.

Historically, the County’s understanding of IPV has been based on national data, which, though useful, fails to capture local nuances that lend greater insight into specific community needs. The county published a report and dashboard to provide more local context to problems of IPV in Allegheny County by describing trends in demographics, human services involvement, and criminal histories among victims and perpetrators of intimate partner homicides (IPH). The report covers January 2017 through September 2022. The dashboard includes more recent information and is updated annually.

The analysis point to a disproportionate impact on individuals who are disadvantaged not only by their gender identity, but also by systemic racial and socioeconomic inequalities. Though IPV has traditionally been framed as an issue related to gender alone, a more intersectional understanding of risk and impact can better inform strategies for effective prevention and mitigation.

Key Findings from Report

- There were 45 victims (43 incidents) of IPV and IPV-spillover homicides from January 2017 through September 2022.

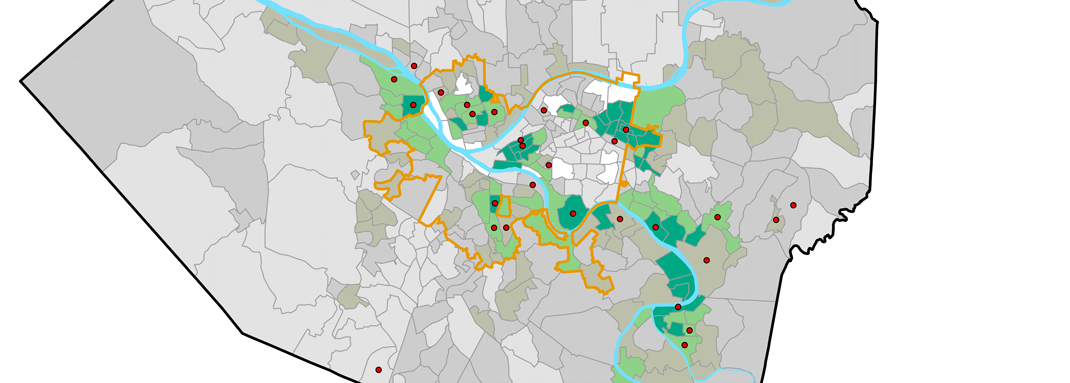

- The demographic trends among individuals involved in IPH are similar to those of overall homicides: victims and perpetrators are disproportionately Black, young (aged 25-34) and living in high-need areas. Black women represent the highest proportion of victims (37%, n=16), while Black men constitute the highest proportion of perpetrators (56%, n=23).

- Unlike homicides at large, IPH victimization disproportionately impacts women: 63% of victims of IPH are women. While IPH accounted for roughly 7% of all homicides from January 2017 through September 2022, they made up 30% of all homicides with female victims.

- Both victims and perpetrators of IPH had high rates of involvement in human services. 74% of perpetrators had prior involvement with child welfare, publicly funded behavioral health, or homeless and housing systems.

- 58% of victims had prior involvement with child welfare, publicly funded behavioral health, or homeless and housing systems.

- Across all gender, race and role categories, about 53% of individuals involved in IPH – 47 of 88 – had criminal justice involvement at some point prior to the homicide incident: 63% of perpetrators (27 of 43) and 44% of victims (20 of 45). Among perpetrators with criminal justice involvement, both Black and White men had higher rates of involvement than either Black or White women.

- Roughly 24% of all IPV perpetrators had indicators of IPV history in either the criminal courts or child protection system. This is likely an undercount of true IPV history, as data limitations, legal restrictions and underreporting make identification of non-fatal IPV in the data difficult. Among those with domestic violence related criminal cases, the majority occurred in the 18 months prior to the homicide incident.